In the summer of 2013, a woman who called herself Rachel Marconi wept. She was an agunah, a chained wife, one of the many Orthodox Jewish women in the world whose husband withheld from her a get, the biblically mandated bill of divorce.

With Rabbi Martin Wolmark on speakerphone from New York, Rachel recounted how she lived piously but remained childless because her husband squandered their money, abandoned her, and refused to grant her a divorce. The inability to obtain a get is no mere inconvenience: A get-less woman cannot remarry within the faith, and any children she might have will not be considered Jewish.

“What is his name?” Wolmark asked.

“Alejandro Marconi,” said Rachel’s brother, Jonathan Miller, who sat with her in the New Jersey office as they spoke to Wolmark.

“Who?” Wolmark said. Marconi is not your typical Jewish name.

“Um, Alex Marconi,” Jonathan repeated.

Rachel jumped in. “Yes, rabbi. He’s from Argentina, although he travels to the U.S. and does business with my brother. That’s how I met him. We were married in 2010. The marriage did not work, for many reasons, which I can get into, but now we’re at wit’s end here, and we’re looking for options.”

“How do you avoid having children?” Wolmark asked.

“He just stopped coming home. He just refused to have sex with me, just abandoned me.” Rachel explained the anguish of her poor mother, who desperately wanted grandchildren. “She wasn’t happy that I married a Sephardic in the first place.”

Wolmark seemed dismissive. “Let’s go back,” he said. “Why doesn’t he want to give you a get?”

“To be honest, he’s not a nice person,” Rachel said. “I’m 43. He knows time is not on my side. He wants to continue taking money from my brother, my sweet dear brother.”

“How much have you given him?” asked Wolmark.

“Fifty thousand,” Jonathan said. “I’m no longer going to be an ATM machine for a man with no morals!”

Wolmark perked up at the mention of Jonathan’s deep pockets. “Well,” he said, “there are two ways to go here, two ways to crack the nut. Under certain conditions, a beit din” — a religious court — “can issue an order of coercion, authorizing public shaming and protests. But that’s rarely successful, especially when the husband lives abroad. There’s another way: Get him to New York, where someone can nail him.”

“I like what you’re saying,” Jonathan said.

“Have you heard the name Mendel Epstein?” Wolmark asked.

“I’m not sure,” Jonathan said.

“Sounds familiar,” Rachel said.

“Mendel’s not a bad guy. He’s a good guy. He can be very helpful, and maybe, in this case, he will.”

For the previous year, “Rachel Marconi” had been the alias of Jessica Weisman, an FBI agent who carried out numerous investigations in the underworld of Orthodox Jews.

A former child actor from Newton, Massachusetts, Jessica’s small stature made her an unlikely candidate for the FBI, even after she spent three years in her mid-twenties working at the Delaware Department of Probation and Parole. But when a fellow student in her PhD program, who happened to be an active FBI undercover agent, asked if she’d ever considered the FBI, she applied, was accepted, and joined the bureau in 1998 as one of seven women in an incoming class of 53 new agents. “I remember the day she left,” said Melissa Kearney, her partner in Delaware. “A male supervisor said, ‘Jessica was a big fish in a little pond. Let’s see how the little fish does in the big pond.’”

When Jessica walked through the door at the FBI, Don Wadsworth’s first impression was that she was an attractive lady but too small for the physical side of the job. Wadsworth ran the FBI’s Program Fraud group, a subset of white-collar crime, and he needed to find a new female agent for the group to replace a retiring female undercover agent. FBI headquarters gave Wadsworth one week to determine if Jessica would be a good fit. The first day, he recalled, there was an arrest warrant out for a bank robber, so he and Jessica drove past the robber’s residence and saw him riding a bicycle. When the perp saw the unmarked car, he took off peddling. Wadsworth planned to cut him off at the corner, but Jessica opened the door, ran up the street, tackled the perp, and had him cuffed by the time Wadsworth arrived. He called headquarters: “She’s going to be a good fit.”

On the undercover beat, Jessica became a Jill of all trades. She went to fancy parties in Europe, where she mixed with fellow spies. With her hair down, she was eye candy for her marks. A ponytail made her look like a kindergarten teacher. A little flirting, she found, went a long way. Closer to home, in the tri-state area, she hung out with white-collar crooks on Wall Street and boiler-room mobsters in Queens.

“Please tell me you’re not going after the Jewish people again!”

At a neo-Nazi encampment out west, where children performed “Heil Hitlers” and swastikas covered the walls, Jessica was playing the girlfriend of the lead male agent when she was called into the kitchen, handed a bucket of bloody horse meat, a grinder, and a box of breadcrumbs and was asked to make meatballs in preparation for a “Viking Odin” wedding. As she worked, the neo-Nazi wives and girlfriends grilled her about her background. She remained calm by focusing on her breath, her usual practice in these tense situations. Without claiming any specific racist views, she said she loved her boyfriend and was still exploring different philosophies.

In real life, Jessica had boyfriends who met with various levels of approval from her mother, Janice. In high school, there had been the sweet all-American lacrosse player who her mother loved. In college, there was the no-neck football player who Janice did not believe was up to Jessica’s level. When she first got into the FBI, she dated a couple of agents, both of them nice, but then along came Dan. “The first time we met Dan was when Jessie organized a picnic for her office at the Coast Guard Station in Cape May,” Janice said. “I said to her, ‘He looks pretty nice.’ She said, ‘We’re just friends.” I said, ‘I’d think that one over.’”

Dan Garrabrant, a former cop, was on his way to becoming the FBI’s top agent for busting sex-trafficking rings and recovering exploited children. (His work was featured in the 2011 book Somebody’s Daughter.) Dan and Jessica got married in 2004 and settled in the Jersey Shore community outside of Atlantic City. They had three children, and Jessica threw herself into cheering at soccer games, selling tickets to school plays, and observing holidays — both Jewish (hers) and Christian (Dan’s). She joined a book club, where, once a month, the neighborhood women discussed novels by Gillian Flynn and Kathryn Stockett. “Oh my gosh!” they’d say, catching up over wine. “You went where? You did what?”

But no one worried like Jessica’s own mother, and Jessica’s safety wasn’t all that concerned Janice. Among Jessica’s emerging specialties was a steady workload of Jewish cases. Many of these cases involved financial crimes. She infiltrated a ring of Orthodox real-estate investors who rigged tax-lien auctions and a group of Orthodox men who ran a pump-and-dump scheme on Wall Street. Some cases were more eccentric, such as the Brooklyn rabbi who purchased black-market organs from impoverished Israelis and smuggled them to the U.S.

“There are plenty of good religious people,” Janice told me, “but there’s an element — certain groups that think they can do anything they want. Their idea of right and wrong can be quite different.” Still, the Jewish cases made Janice uneasy; a piece of her worried about what people thought when they saw headlines reinforcing the old stereotypes: fraud and corruption.

“Please tell me you’re not going after the Jewish people again!” Janice would say to her daughter whenever she saw the telltale black dress hanging in Jessica’s laundry room.

Jessica knew these cases gave a bad name to Jews, and she hated that aspect of the work. But every community had its criminals. And no one, she believed, should be permitted to take advantage of the weak or the helpless, whether financially or through violence, no matter how it was rationalized.

If New York is a capital of culture, where the young come to test life’s possibilities, Orthodox New York is another city. This is the New York where it is easy to find charity but hard to buy a book about science or history. Here, in the parallel city, boys who have never heard of Sandy Koufax trade rabbi cards and tape beards of white cotton balls to their chins on the holiday of masquerades. In this city, where the old ways will always outlive the latest lifestyle, it is said that every outsider hates Jews, even those who pretend not to. The city where innocence is righteousness — where The Word is pored over while life’s complexities go unconsidered. The city of well-curled sidelocks and Saturday stew and girls for whom all promise comes down to a stiff wedding dress and the giving of an unperforated hymen to a young man so pure he will refrain from touching her for at least 12 days following the onset of menstruation, will never let his hand go below his own waist, and will spend a full night in Torah study, dusk till dawn, to atone for a wet dream.

In this New York, according to the defection memoir Unorthodox by Deborah Feldman, a good rabbi is the one who can find the heter, the loophole in the law.

“For Jewish fundamentalists, he was a hero because he made the system work. And the system has to work, remember, because if the Torah is right and just, then its law can’t be wrong.”

By the law of divorce, a man cannot be coerced into giving his wife a get unless rabbis deem his refusal to be unjust. In that case, the get-refusing husband may — according to Maimonides, the 12th-century codifier of Jewish law — be beaten until he comes to his senses. But most rabbinical courts refuse the nuclear option and favor the man in divorce.

Against this unbending patriarchy, many Orthodox women saw Mendel Epstein as a white knight.

This reputation began in the 1970s, when Mendel, then a young rabbi, ran a school for Orthodox girls. Young couples often sought his advice on how to raise their children. When the divorce rate spiked, those same couples asked him for guidance in divorce. In his role as an informal divorce counselor, Mendel watched husbands use Jewish law as a weapon against their wives by refusing to give them a get. Men withheld the get because they were bitter or because they wanted money or a favorable custody arrangement — or all three.

According to the government, Mendel’s racket of scaring unwilling husbands into giving their wives a get started around 1980. “It was mostly intimidation,” Mendel told me. “Just talking to them.”

Back then, Mendel, who is 6 feet, 3 inches tall and burly, traveled frequently to Café Baba, a kosher belly-dancing club in Queens that used to be a popular destination for Israeli ex-pats who left their families and refused to give their wives a get. Mendel would carry a photo of a man’s wife and children, approach the get refuser as he ate and drank with half-naked women, and say, “Can we speak? I have a message from your wife and your children.” When the man protested, Mendel would say, “Sign the get, and you’ll never see me again.”

All over the city, from Wall Street offices to Lower East Side delis to docks in Red Hook, Mendel was cursed loudly by recalcitrant husbands. But he usually came through with a signed get and saved another Jewish woman from life as an agunah, a chained wife.

By 1986, Mendel was telling get activists that some cases of get refusal merited the “death penalty.” Did he mean it? Hard to say. Rabbis were notorious for hyperbole, and Mendel was the kind of rabbi who said lots of things. But he was serious about expanding his reach in the get business. In the Jewish Press, an Orthodox newspaper, he wrote a column called “Chained,” offering advice to divorcing women. The column then became the basis for his 1989 book, A Woman’s Guide to the Get Process, in which he wrote: “Personally, I’d prefer the guillotine for any individual who ruins and imprisons another human being for monetary gain.”

Around the time the book was published, Mendel recruited his rabbinical colleague, Martin Wolmark, to join in his work. Ten years Mendel’s junior, Wolmark was the son-in-law of Zev Wolfson, a wealthy real estate magnate and noted philanthropist. Soon they added more rabbis to their gang, forming what a prosecutor would later call the Get Crew, and their methods became more extreme: abductions, broken bones, cattle prods.

But aside from the occasional angry husband outside of Mendel’s home in Flatbush, where he lived with his wife and their nine children, and aside from the occasional slashed tire or dead fish on the porch, Mendel was considered a necessary if unpleasant feature of Orthodox life. “For Jewish fundamentalists, he was a hero because he made the system work,” said Susan Aranoff, a longtime get activist. “And the system has to work, remember, because if the Torah is right and just, then its law can’t be wrong.”

An accountant attacked with a baseball bat! An attorney shot through the thigh! Cattle prods! Facial burns! Hearing loss!

Mendel was never wrong; not in the parallel city or mainstream New York. Any problems that secular society has with Orthodox traditions — from the way they slaughter chickens to the way they circumcise babies and educate children — are effectively mooted by the community’s enormous voting power. So when irate husbands ran to secular authorities, they found no quarter there. In the late 1990s, one husband who claimed to have been pulled into a van and beaten, pushed the Brooklyn district attorney’s office to bring charges against Mendel. Stories emerged in the secular press. An accountant attacked with a baseball bat! An attorney shot through the thigh! Cattle prods! Facial burns! Hearing loss! When the case was dismissed without explanation, Mendel told Newsday, “I’m the champion of gittin!” — the plural for get.

But by then, his white-hatted vigilantism had morphed into something darker. “For years, I watched Mendel do things for free when people couldn’t afford to pay,” Wolmark told me. “He was totally engaged by right and wrong. But he never had money. Always struggled to pay his debts. Then he lost a son. Then a son-in-law died and left his daughter with 10 children. And so it was around the late nineties when he started to represent whoever paid the most, including men — some real pieces of garbage. That’s when he lost support in the community. People who thought he was in it for the message of God saw that he was just another Joe, out there for the buck.”

Mendel knew that Wolmark looked down on him, but it was easy to be Wolmark, he believed, easy to be married to Zev Wolfson’s daughter and have millions in the bank. Besides, Wolmark’s own immediate family wasn’t exactly clean: His brother would eventually undergo federal antitrust prosecution for his role in a billion-dollar Wall Street scheme, rigging auctions for municipal bonds. As for lawyers flipping sides in standard, nonviolent divorce proceedings, choosing to represent whoever could pay the most, Mendel rationalized that secular attorneys did it all the time.

Walking on the streets near his homes — by the early 2000s he had two, in Brooklyn and Lakewood, New Jersey — he was feared and respected. His family — which grew to more than 50 between children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren — received special treatment in stores, as if the Epsteins were royalty or gangsters. People came to Mendel with their problems, and, like Johnny Cash’s man who came around, Mendel decided who to free and who to blame in the everlasting get wars. Till Armageddon no shalam, no shalom.

His impunity might’ve lasted forever, had it not been for the bizarre case of Meir Bryskman.

In the summer of 2010, Meir Bryskman came to the Lakewood police station covered in cuts and bruises.

Bryskman had fled Israel a few years earlier because his wife wanted a divorce. His name appeared in Israeli newspapers as a get refuser. His brother-in-law had tried to kill him. On the lam as a get fugitive, he bounced around Orthodox circles in New York, looking for work, when a Lakewood man named David Wax offered him an interview for an editorial job at a religious publishing company. Bryskman told the police that when he appeared at Wax’s home, Wax and Wax’s wife lured him upstairs, where he was bound, beaten, and kicked in the ribs for hours. At one point, Bryksman said, Wax put on a cowboy hat, permitted Bryskman to look under the blindfold, and said, “How do you like my hat?” He said someone poured vodka down his throat as they questioned him about his finances and told him they had a “plan B” for him: a grave in the Poconos, where they would bury him alive and videotape rats eating his body. When the carpet became soaked in blood, Bryskman recounted that Wax yelled, “You ruined my carpet!” According to Bryskman, after a visit to an ATM machine resulted in a failed attempt to get money from Bryskman’s bank account, Wax tried to extort money from Bryskman’s Israeli father (who recorded the call), then dropped Bryskman off in Brooklyn.

The next day, when Bryskman told his story at the Lakewood police station, police filed charges against Wax and his wife for kidnapping and assault. When the charges became public, calls poured in from the Orthodox community: Wax, people claimed, was part of a larger crime syndicate, a global get mafia headed by Mendel Epstein, who was now outsourcing beatdowns and taking a cut of the fee.

The fact that the Waxes drove Bryskman from New Jersey to Brooklyn meant there was an interstate nexus — a federal case — and the Lakewood police called the FBI. Special Agent Bruce Kamerman — a Jew from Staten Island and a former Marine Corps lieutenant — looked at the file and got excited: Here, Kamerman hoped, was an opportunity for a racketeering case. The RICO statute enables agents to pursue not just violent actors for singular crimes but entire criminal enterprises. And under RICO, there is no statute of limitations: a prosecutor can charge for crimes that occurred as far back as the origination of the statute itself, which — according to David Wax, who flipped and became an informant — happened to be right around the time that Mendel Epstein started beating people up, three decades earlier.

But Kamerman had a big job ahead of him. He had to find victims and evidence that linked the beatings to Mendel Epstein, who had not been physically present at beatings for years. Kamerman, pursuing a fact-finding mission in one of America’s most closed communities, found many victims but little evidence of an organizational hierarchy. Kamerman saw his RICO case slipping away — until a new get-refusing husband appeared, someone who’d not yet been accosted but was likely about to be the subject of a beating.

For several years, Aharon Friedman, a Washington, D.C., attorney, had been under public pressure to give his wife a get. Rabbis issued threats.

People protested outside of Friedman’s home and office. There were even New York Times articles about his divorce proceedings. When Friedman tried to attend synagogue in Maryland, his brother-in-law incited a riot against him. His wife, who retained Mendel Epstein, was interviewed on NPR.

In the summer of 2012, Friedman, 34, drove to Brooklyn to meet Naomi Mauer, owner of the Jewish Press, an Orthodox newspaper. Mauer was in her seventies but still edited the section of her newspaper that featured recalcitrant husbands, a kind of “wanted” page for get refuseniks. Friedman, the refusenik, told Mauer that he wanted his photo removed from the dreaded page. He said that he was only asking his wife for better visitation with their five-year-old daughter.

Mauer had heard it all before. In 1993, Mauer’s own divorce landed as a feature in New York magazine, where it was reported that her husband chased her around their Manhattan Beach home blowing a shofar into her ear while insisting that Mauer’s father give him 50% of the Jewish Press in exchange for the get. Back then, Mauer refused Mendel’s offer to beat her husband because she was concerned with the effect such a decision would have on her children. But how many women had she referred to Mendel over the years? Too many to count. Aharon Friedman didn’t faze her.

“Give her the get, and we’ll take you out of the paper,” she told him. “You’re young, handsome. You have a good job. You’ll find another.”

“I’m in Jewish Press as a get refuser! What woman will want me?”

“I guarantee there are women who’ll believe that your wife was a B-I-T-C-H, and that you were justified in trying to convince her to stay. When you saw that there was no use, you gave the get. Don’t ruin your life.”

As a Harvard Law School grad who clerked for the Israeli Supreme Court and now worked for a congressman in Washington, Friedman was not accustomed to losing an argument. After Friedman walked out, Mauer called Mendel. Mendel hadn’t orchestrated the meeting between Mauer and Friedman, but Mendel was aware the meeting was taking place. She wanted to let him know she’d been unable to sway the refusenik by peaceful means: “No luck.”

Friedman knew his wife had retained Mendel Epstein, but he refused to be intimidated or back down. When he heard of the FBI investigation, he approached Bruce Kamerman, who saw a chance to dangle Friedman in hopes of gathering another victim for the case. Kamerman made it clear that the FBI couldn’t provide Friedman with security. Kamerman recommended protective measures and said, “Be safe.”

July 29, 2012, was Tisha B’Av, the Jewish day of mourning, when Friedman returned his daughter to his mother-in-law’s home. The transition struck Friedman as strange. Usually, his mother-in-law’s car was in the driveway, but now there was only a minivan. Then, at the door, his mother-in-law asked him how his daughter was, which was weird because his mother-in-law hadn’t spoken a word to Friedman in years. Walking down the driveway to the street, Friedman noticed two men, one wearing a Halloween mask and the other wearing a ski mask. Friedman ran as fast as he could, but one of the men caught up with him and clocked him on the back of his head. He fell to the ground, lost his yarmulke, got up, took a defensive stance, and screamed as loud as he could. When one of the men punched him in the face and broke his glasses, Friedman reached into his jacket and pressed the button on a 5Star Responder, a device that sends an emergency alert to 911, which in turn contacted Kamerman at the FBI.

Kamerman added Friedman to the witness list. But the links to Mendel Epstein and the Get Crew were still too attenuated. Kamerman spoke to a prosecutor. They agreed that the only way to make a case would be through an undercover operation, and they both thought of the same agent for the job.

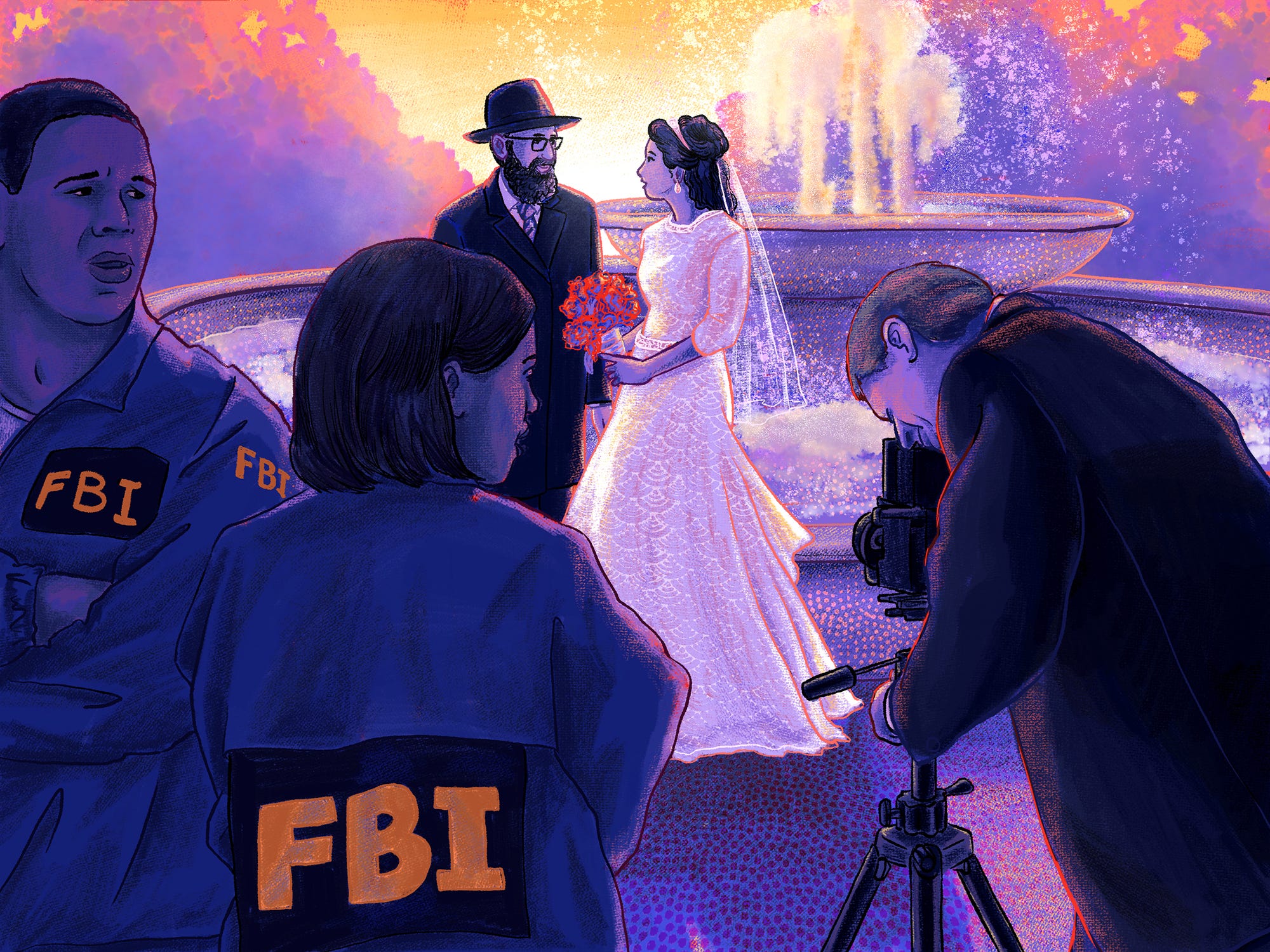

In the late summer of 2013, Jessica Weisman pulled out the black dress. For the previous year, she had been working with the FBI’s informant, David Wax, to build her cover story as an agunah. None of the agents liked Wax. He had a big ego and told whatever lie suited him in the moment. “You don’t pick your family, and you don’t pick your witnesses or informants either,” Kamerman told me. “You take what you get, warts and all, and, boy, was Wax a piece of work.”

But Wax knew the Get Crew. He advised Jessica on how long her dress should be and what kind of head covering she should buy. Based on his advice, the agents decided against a “cold bump” — trying to reach Mendel on their own without an introduction. They planned an organic operation in which they would lay all the necessary groundwork to backstop Jessica’s undercover identity and substantiate the backstory of her marriage. Jessica read Mendel’s book, A Woman’s Guide to the Get Process, and learned that among Ashkenazi Jews in the Orthodox community, there was a bias against Sephardic Jews, so she had the idea to make her fictional husband Sephardic in order to gain more sympathy from the rabbis. Argentina has the world’s fifth-largest Jewish population, much of it Sephardic, and the FBI happened to have a 57-year-old Jewish undercover agent in Buenos Aires, Marc Ruskin, whose alias was Alejandro Marconi.

Normally, undercover identities are backstopped by fake driver’s licenses, Social Security cards, credit cards, and other “wallet filler,” but in this case, Jessica, going as Rachel Marconi, would need something extra: the indicia of an Orthodox marriage. So the FBI forged an aged-looking ketubah, the marriage contract. The entire undercover team flew to Buenos Aires, where they met with a Sephardic rabbi, staged photos of Rachel and Alejandro getting married at a synagogue, and took more photos of their reception at a kosher restaurant.

When Rachel returned to New Jersey, she could converse comfortably about where she worshipped, socialized, and shopped in South America. She was a 43-year-old wife whose Argentinian husband refused to give her children, ran up debt, abandoned her, and withheld the get while extorting money from her wealthy brother, Jonathan Miller, played by Special Agent Jon Weiss, who looked like he was related to Jessica and happened to also be from her hometown of Newton.

Before getting to Mendel, Rachel and Jonathan had to create a paper trail showing that they’d attempted to seek a divorce peacefully. First, they went to an advocacy group called ORA, the Organization for the Resolution of Agunot, where they met with Keshet Starr, a young lawyer who believes that the get itself is a form of domestic abuse. As ORA director, Starr was in regular phone contact with Mendel to brainstorm about difficult cases. On one case, Mendel and Starr would agree: The wife is getting screwed. She’s 36. Time is running out. Then they’d turn to a new case, and Mendel would suddenly switch sides, arguing for the husband, even though the facts were similar to the previous case: She has to be patient. She’s being ridiculous about money. “I was surprised to learn that an earlier generation of women had ever considered him to be an advocate for agunot,” Starr told me. “I always thought of him as the classic shark attorney. If he was on your side, he was the best. If he wasn’t, he was the devil incarnate.”

The average ORA client was much like Rachel Marconi — aging, childless, several years into a split — and yet Rachel struck Starr as a little off. There were common Hebrew words that Rachel didn’t know, for instance. But Starr didn’t think much of it — ORA was a social-service agency after all, and she fielded calls daily from people who seemed off. Starr referred Rachel to the Beth Din of America, where she petitioned the religious court for summonses to be sent to her husband. When the summonses were sent but never responded to, the agents felt they had laid enough groundwork to approach Mendel via his go-between, Martin Wolmark.

At first, Wolmark was dismissive, but Rachel’s desperation combined with her brother’s deep pockets did the trick, and in that first phone call, Wolmark did what the agents only dreamed of: conferenced in Mendel, who listened and said, “Sounds like it’s not a call,” referring to the risk of speaking about kidnappings and assaults over the telephone.

So in August 2013 — nearly three years after Bruce Kamerman launched his investigation — Rachel and Jonathan knocked on the door of Mendel’s home in Lakewood. One of Mendel’s daughters, Batsheva, welcomed them at the door and escorted them to a study, where Mendel sat behind a large desk beneath photos of famous rabbis. Outside, in the fenced-in yard adjoining his son’s house, dozens of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren played.

He told the agents, who were both wired, “I don’t want to use any secular terms, but what we’re doing is basically kidnapping the guy for a couple of hours, beating him up, torturing him, and then getting him to give a get.” He added, “I do this cause there’s no one else who wants to do it and get it done the right way. My wife’s not too happy. She says, ‘You have a good life. What are you doing this for?’ But I feel that sometimes there’s just no solution. We try everything and it just doesn’t work.” He alternated, he explained, between his “rabbinical hat” and his “criminal hat.”

Rachel knew, of course, that husband-victims were often left with bruises and broken bones, but she wanted to elicit talk of the cattle prods, so she asked, “How do you do it without leaving a mark?”

“You really want to know?”

“Yes.”

“Take an electric cattle prod. If it can get a bull that weighs five tons to move, you put it in certain parts of his body, and in one minute, the guy will know.” Mendel stroked his white beard, smiling at memories of past triumphs. “Karate also works well. We’ve learned on different people how to do this. The first shot, if you land it, puts him out. Whether it’s a kick to the stomach or a bat. My guys? They don’t meet with him and say, ‘Let’s do this nicely.’ That’s not the style. A minute ago you were standing there like a normal person. Now you’re lying on your back with handcuffs and a bag around your head. Then zap! And he goes nuts!”

He said that on average he did one strong-arm case per year, and the price was $70,000.

Mendel discussed the impunity he enjoyed among secular authorities and the power wielded by the Orthodox community in Lakewood. “The blacks are mostly gone ’cause we won’t hire them to watch our kids or do anything,” he said. “We do like the Mexicans because they’re family-minded.” He bragged about his reputation among the Italian mafia and recounted how the Gambino crime family had once hired him to collect debts. He said that during meetings with the Gambinos, they would always be cleaning their guns. “Once, they asked me to become a mediator between the families. I said, ‘One question: How long did the last mediator live?’”

They all laughed, and Rachel asked, “Do your guys carry guns too?”

“Cattle prods,” Mendel said.

Through the late summer and early fall of 2013, there were more meetings and calls and emails. During one call, Rachel nearly blew her cover when her son came running into the room yelling, “Mommy!”

The final meeting was held at Wolmark’s office in Monsey, New York.

Why, he wondered, did the FBI care about Jewish divorce, about defending a woman against a bully?

Rachel and Jonathan met with Wolmark, Mendel, and another longtime Get Crew member, Jay Goldstein, the gang’s sofer, who wrote the gets and helped administer beatings. After getting through the formalities of how Alejandro would be lured to a warehouse, Rachel asked, “Is there a time period I should wait, or can I date right away?”

“You’re not allowed to get married for three months,” Mendel said.

“Just don’t kiss in public,” Goldstein added. “That’s all. If you were younger we’d give you a little more time to wait, but…”

“I know, time is not on my side.”

“But do your research on the next guy,” Mendel said.

And with that piece of relationship advice, it was agreed: Rachel’s husband would travel to New Jersey the following week, expecting to collect money from Rachel’s brother, who would lure him to a New Jersey warehouse where the Get Crew would be waiting.

While Jonathan pulled the car around, Rachel and Mendel stood outside, and Mendel said, “We probably should’ve looked into your background more. I’m kind of upset with Wolmark. I thought he’d done some vetting. … You know what? It’s too late now. I’m getting too old for this. What did you say you do for a living again?”

“I work in the tax lien industry,” she said.

“I have a friend who did that. David Farber. It’s a great business.”

Rachel froze. She put David Farber in prison on the tax-lien sting. She focused on her breath and said, “Yep, it’s a very good business.”

Two hours later, Jessica still had the black dress on when she picked her daughter up from preschool. As much as their kids knew what she and Dan did for a living, as often as they’d seen mom and dad come home from work each day and put their guns in the safe, they still didn’t really know, nor did they care: a big takedown, a serious case — it didn’t mean anything to the children. “Mom,” her daughter said, “what’s for dinner tonight?”

On October 9, 2013, a minivan pulled up to an office complex in Raritan, New Jersey. In the backseat, Goldstein, the sofer, scanned the parking lot and saw nothing suspicious. The 60-year-old wore a Metallica T-shirt, and with him in the minivan were six schlammers — the young thugs who administered the beatings, two of whom were Goldstein’s sons — and another rabbi who was attending as the ceremonially required witness. Their gear included razor blades, a screwdriver, a headlamp, a bottle of vodka, and feather quills and black ink for the writing of the get.

Inside the office complex, they met Jonathan, who showed them around as they planned out the details of the assault. Alejandro would arrive, and when Jonathan said the word “fuck” in Spanish, the schlammers would come out of hiding.

The schlammers shadow-boxed, stretched, and prepared. One pulled on a black ski mask. Another wore a ghoulish Halloween mask. A third wore a hoodie and sunglasses and covered his face with a bandana. A fourth lacked a bandana, so he tied a plastic bag around his face. They milled about, looking at different rooms. They didn’t like the conference room because it had a window.

“It looks kind of funny, no?” Goldstein said. “We’re walking around with masks. Turn the light out. Is there a room with a door? That way, if somebody shows up, we could close the door and keep him quiet.”

“I like the bathroom,” said one of Goldstein’s sons. “As long as there’s no place he could jump out of a window. I had a guy once jump through a closed door.” Another schlammer reminded the others not to leave DNA behind.

They were ready for action when 40 arresting agents burst in.

“FBI! FBI!”

The schlammers hit the floor. Goldstein was gobsmacked: There was gang warfare and violent street crime all over the city — why, he wondered, did the FBI care about Jewish divorce, about defending a woman against a bully?

Meanwhile, in Lakewood, Mendel was equally surprised when agents raided his home. Later, at the FBI office, he was furious when he saw Rachel Marconi walking the hallway in the street clothes of Jessica Weisman. “You’re a Jew!” he screamed. “How can you do this?”

Six of the ten people on the indictment pleaded guilty, including Wolmark and Goldstein’s two schlammer sons. The other four defendants — Goldstein himself; Mendel and his son David; and Binyamin Stimler, the psychologist-rabbi who had attended as the witness — took the case to trial.

The case didn’t look good for the Get Crew. During the trial, the prosecutors portrayed the rabbis as mafia bosses. The headline, even though cattle prods were never found, was “Prodfather.”

But then things changed: Over the course of the two-month trial, much of the myth surrounding Mendel was never proven. To Special Agent Bruce Kamerman’s dismay, the U.S. attorney’s office declined to charge the defendants under the RICO statute. Prosecutors didn’t believe they could show the existence of an organizational hierarchy or demonstrate the necessary links between the defendants going back decades. So they charged them instead with four kidnappings.

At the trial, four beaten husbands, including Aharon Friedman, testified, but none of the husband-victims seemed credible. One was so evasive that the judge compared his testimony to a Saturday Night Live skit. During testimony from the government’s lead informant, David Wax, the judge all but confirmed to the jury that Wax was a liar and a fraud.

Looking on from the gallery, Jessica’s mother, Janice, felt ashamed and embarrassed. Most jury members, she imagined, knew little of the Jewish people. What were they going to think?

The government claimed that on the night of one man’s abduction, Mendel’s son David was present, but David had an alibi. So the jury convicted only three of the four defendants and only on charges related to the sting itself. In the end, the government failed to prove that Mendel Epstein completed a single criminal act — only that he agreed to do so when approached by FBI agents.

At Mendel’s sentencing, he addressed Judge Freda Wolfson, who was of no relation to Wolmark’s father-in-law but whose Jewish heritage, Mendel hoped, would bode well for the Get Crew at this critical moment.

“When I listen to the tapes, I am embarrassed and ashamed,” he told the judge. “I’m in the midst of a root canal without Novocain. I got caught up with my tough-guy image. It helped me, honestly, the reputation, to convince these reprobates to do the right thing. There were times, I admit, when situations got out of hand. And I never should’ve asked for money. It makes me look like a fool. I do, however, have to my credit thousands of children born because these women were allowed to start a new life. That is my legacy.”

Wolfson said it was “nice” that Mendel felt good about what he did, but she said he was no different than any crime boss — a businessman who isolated himself from risk even as the high rates he charged remained in his own pocket, with the young schlammers getting $300. Wolfson sentenced Mendel to 10 years. The schlammers pleaded guilty and got between three and five years each. Wolmark, the fixer, pleaded guilty and served 21 months. Goldstein, the sofer, got nine years. And Wax, the informant, was sentenced to eight years.

Kamerman was upset about the sentencings. “The whole message you want to send to the community is that there is a benefit to cooperating,” he told me. “What Wax did was reprehensible. But by all accounts, he was only involved in one of these things whereas Mendel admitted to doing one per year for three decades.”

“These guys I dealt with, their world — that’s not the normal Jewish world.”

At the federal prison in Otisville, north of New York City, Goldstein is imprisoned with his two sons and shares a cell with a third schlammer, Simcha Bulmash, who had been heading to medical school when he got arrested with the Get Crew. From prison, Goldstein wrote to me, “This country was founded on the principle of being a haven for oppressed people. It’s a travesty to use the law to protect the ‘innocent husbands’ who tyrannize others. Sometimes you have to use common sense, and not just go by what’s written in a book.”

But even within Orthodox circles, there was little agreement about tyrants and victims. During the trial, Mendel’s daughter Batsheva wrote an open letter to the Orthodox community beseeching them to pray for the defendants as they underwent persecution from a government that “cannot see past the star on our arms, the tattooed numbers on our skin. Their endgame is to imprison as many Orthodox Jews as they can.” On Frum Follies, the website where she posted the letter, commenters reminded her of the times that she and her “gangster father” sold out wives who couldn’t afford to pay extortionate rates, either refusing to represent them or representing their husbands instead. The Get Crew, commenters said, cared only about power and making money on the pain of others and the broken Orthodox divorce system.

And still, those same commenters acknowledged that the plight of chained women had worsened since Mendel’s arrest. No longer, one commenter wrote, did “sadomasochistic husbands fear that their wives would avail themselves of Option B.”

Plenty divided the people I interviewed about this case. But what connected most of them — from friends and foes of Mendel to the get-refusing husbands — was unshakeable hypocrisy. Aside from get activists, only one person I interviewed, a pediatrician named Max Bulmash, father of the imprisoned schlammer Simcha Bulmash, said that Jewish law should be changed. “You can’t use the Torah as a weapon to make a woman suffer,” said Bulmash. “There’s no way that could be Judaism. It’s time for the system to be revised.”

But even Mendel himself refuses to entertain the idea of revising the law.

During the 18 months that Mendel and I exchanged correspondence, he referred to Judge Freda Wolfson as “the pork-eating judge” and reiterated the superiority of Orthodox culture. “What scares outsiders,” he wrote, “is our ability to organize. Think about it: If black athletes gave 10% of their earnings back to their people, there’d be a major dent in the war on poverty.” This way of thinking was the defining feature of Mendel Epstein’s parallel city: a general disdain for the unworthy.

In prison, he has a congregation again, a growing group of incarcerated Jews with whom he studies and prays, taking three steps backward and three steps forward, bowing low to say, “O, behold our affliction and wage our battle … support those who fall, heal the sick, unchain the imprisoned…”

“These guys I dealt with, their world — that’s not the normal Jewish world,” Jessica Weisman told me. “They don’t represent the good Orthodox people in this country. These women, the wives, they were either going to be extorted by their husbands or by the rabbis. The rabbis see themselves as kind toward their own. That’s ridiculous. It’s all about the money.”

Jessica remains a star at the FBI. In the spring of 2020, her 50th birthday will mark her first possible retirement date. With her kids approaching college, she had considered leaving the bureau and finding a more lucrative career until earlier this year when the FBI appointed her head supervisor of the Atlantic City division, making her the first woman to lead the office of 70 people.

Jessica used to believe the greatest job for her was being a rank-and-file field agent and that a management position would never suit her personality, but after 20 years in the underworld, she figured she should try to pass on some of what she’s learned. Whether she’ll return to an undercover role remains to be seen, though now she enjoys teaching agents and organizing task forces. The last time we spoke, earlier this month, she was coming home from a satisfying day. Following a long investigation, the mayor of Atlantic City pleaded guilty to stealing $87,000 from a youth basketball fund. When asked if she’d still consider retiring early, she said, “I won’t find anything better than this.”

Her mother, 84-year-old Janice, was happy about Jessica’s promotion because she imagined it meant that her daughter would work less and slow down. That hasn’t turned out to be the case. But at least the black dress remains on its hanger, tucked inside a New Jersey closet. For now.

https://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/rabbis.pdf